Understanding grid balancing & congestion management

Grid balancing keeps the national grid’s frequency stable by matching supply and demand, while congestion management prevents local grid overloads. These two systems can conflict, as solving a national issue might create a local one.

The rapid growth of wind and solar power across the Netherlands (and other European countries) is a fantastic achievement for the energy transition. But this success introduces a new challenge: unpredictability.

Because the wind doesn’t always blow and the sun doesn’t always shine on cue, these fluctuations can strongly stress the grid, which creates problems that our legacy energy system was not originally designed to handle. To manage this, grid operators are focused on two primary, and very different, missions:

- Grid balancing: Keeping the national grid stable.

- Congestion management: Keeping local grids from overloading.

Both are necessary for a reliable energy supply, and both require adjusting the power of flexible assets. However, they solve different problems and can sometimes directly come into conflict.

This article breaks down the difference between grid balancing and congestion management, how they work in the Netherlands, and why this conflict is important to understand.

1. Defining grid balancing and congestion management

1.1. Grid balancing: ensuring matching supply and demand

What is balancing?

The primary goal of balancing is to maintain the grid frequency at a constant 50 Hertz. This frequency relies on the equilibrium between power supply (generation) and power demand (consumption).

When there is an excess of power generation compared to consumption, the frequency goes up. Conversely, if there’s not enough power to meet demand, the frequency goes down. This disparity between generation and consumption is referred to as imbalance.

Thus, to prevent imbalance, supply and demand must be continuously matched in real-time. Maintaining this equilibrium is necessary for grid stability, as any imbalance (+/- 0.2 Hz) can lead to blackouts and other disruptions.Few years ago, a political dispute between Serbia and Kosovo has disrupted Europe’s synchronized power grid, causing clocks that rely on the grid’s frequency (such as those in ovens and alarm systems) to run six minutes slow since mid-January. The issue stems from Kosovo using more electricity than it produces, with Serbia failing to compensate for the shortfall, leading to a continent-wide frequency drop (in other words: imbalance!).

Source: Guardian Staff and Agencies. (2018, March 8). European clocks lose six minutes after dispute saps power from electricity grid. The Guardian.

In the Netherlands, the first line of defense is a system of ‘balancing responsibility’, where the Balance Responsible Parties (BRPs).In Dutch: “Balansverantwoordelijken”

A Balance Responsible Party (BRP) is an entity in the electricity market responsible for ensuring that the amount of electricity produced, consumed, and traded in its portfolio is balanced.

This means the BRP must match supply and demand as closely as possible and is financially liable for any imbalances that occur in its portfolio.

More info on BRPs on TenneT’s website. work to maintain it. However, if the BRPs, and the market, fail to maintain this balance, the Transmission System Operator (TSO) must intervene.

How does balancing work?

Every energy supplier or buyer connected to the grid must be associated with a BRP, which is responsible for keeping its own portfolio of customers and assets in balance.

To uphold the balancing responsibility principle, the BRPs are obligated to provide TenneT with information about their planned production, consumption, and trades for the following day through e-programmes.

Deviations from this program might happen, in which case the BRPs must rectify them before the end of the corresponding imbalance settlement period (ISP). This period, lasting 15 minutes, is when imbalances are calculated and settled.

For this, BRPs have the possibility to trade energy surplus or deficit with other BRPs on markets. In case of a remaining imbalance in their portfolio, BRPs have to face financial consequences.

When the market fails: TenneT steps in

But what happens if the combined actions of all BRPs fail to keep the grid stable?

If total supply and demand across the country fall out of sync and lead to change in the frequency, TenneT must intervene by using balancing products,Also known as “balancing resources”, balancing products can be provided by various market participants, including power plants, batteries, and aggregated distributed energy resources, as long as they meet specific technical requirements.. These products are procured in advance, but are only used reactivelyThese products are traded and activated through the Dutch balancing market, where providers are either paid for keeping capacity available (capacity remuneration) or for actual energy delivered when imbalances occur (energy remuneration) – in real-time when imbalances occur.

These products are facilitated by participants called Balancing Service Providers (BSPs),Balancing Service Providers (BSPs) do not need to own the generator or storage themselves. BSPs can contract with others (such as residential consumers, power plant owners, or storage operators) to offer their flexibility or capacity for balancing services. This means a BSP may aggregate and offer the combined flexibility from multiple third-party assets, provided each of these assets has completed the required pre-qualification with the TSO. who will use their own portfolio of flexible assets — like your batteries, wind turbines, or solar farms — to quickly provide more or less power and help stabilize the grid frequency.

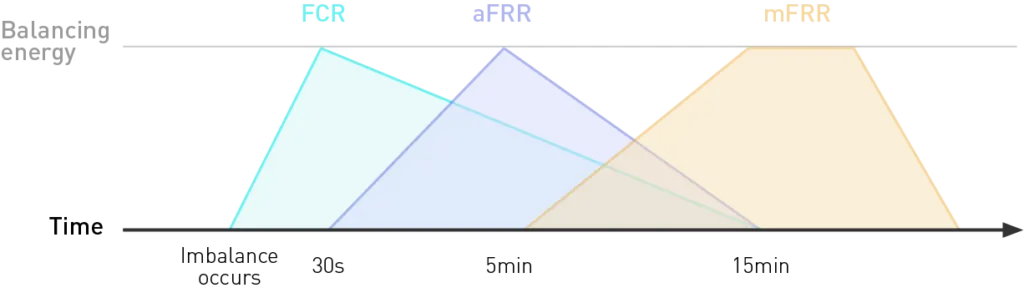

In the Netherlands, there are three main types of balancing products:

- Frequency Containment Reserves (FCR): Also known as the “primary reserve,” it automatically activates in less than 30 seconds in case of imbalance and remains active up to 15 minutes.

- Automatic Frequency Restoration Reserve (aFRR): Or the “secondary reserve”. It is activated by the TSO’s signal, must start within 30 seconds and has a full activation time of 15 minutes.

- Manual Frequency Restoration Reserves (mFRR): Referred to as the “tertiary reserve”. It must be manually activated within 10 minutes (for downward capacity) or 15 minutes (for upward capacity). From this moment, the capacity needs to be able to stay activated for at least 60 minutes.

1.2. Congestion management: mitigating grid overload

What is congestion management?

Congestion refers to situations where the local grid infrastructure experiences limitations in the transmission capacity. It happens when the flow of electricity exceed what the grid can handle without surpassing the thermal, voltage, and stability thresholds. There are multiples risks associated with it, from inflated operational costs to the risk of blackout.

In the Netherlands, this responsibility is split:

- TenneT (TSO) manages congestion on the high-voltage transmission grid (110 kV and above).

- DSOs (like Enexis, Liander, and Stedin) manage it on the local distribution grids (below 110 kV)

What are the different congestion management strategies?

The traditional approach to congestion management was simple: build more cables (grid reinforcement). But that involves significant capital investment.For instance, the Dutch grid operators planned investments of over €8 billion annually through 2026 to expand energy networks amid rising demand.

Source: Netbeheer Nederland. (2023, November 1). Netbeheerders presenteren recordplannen en stellen andere aanpak voor. Netbeheer Nederland. and, most importantly, it’s slow. Grid reinforcement projects are held back by a shortage of technicians, rising material costs, and long delays for permits and land access. We simply can’t build our way out of this problem fast enough

Because of this, grid operators must use smarter, faster mechanisms to manage congestion on the grid we already have.

Capacity Limitation Contracts

Capacity limitation contracts,Called “capaciteitsbeperkingscontract” (CBC) in Dutch.

Read our complete explainer here: What is a CBC contract? (CBCs) are agreements with > 1MW connected parties to limit their use of connection and transport capacity in exchange for a pre-defined financial compensation.

Grid operators can request this curtailment from several days in advance up to the morning before the expected congestion.

Redispatch

Redispatch is a more dynamic, real-time tool used after the day-ahead market has already closed. Here’s how it works:

1. A grid operator identifies an upcoming local bottleneck.

2. It requests a Congestion Service Providers (CSPs)A CSP is a market participant (such as a business, energy producer, or aggregator) that offers flexible capacity to help grid operators manage and resolve grid congestion.

CSPs do not need to own the assets they control but must have the ability (directly or by aggregation) to reduce or increase consumption or production in response to operator instructions. inside the congested area to adjust their plan (e.g., feed in less power).

3. To keep the national grid balanced, the operator must find an opposite adjustment outside the congested area (e.g., asking another party to feed in more power).

In the Netherlands, redispatch is market-based and is done through two two market platforms:

- RESIN: Reserve for Other Purposes (ROD)

In case of congestion, TenneT can deploy Reserve Power Other Purposes – or “Reservevermogen Overige Doeleinden” (ROD) via a system called RESIN. For ROD, Tennet is the single buyer, and the product is location-specific.

Market participants with a connection capacity of 60 MW or higher are required to submit bids to this system.Source: Netcode Article 9.19 For those of a capacity of more than 1 MW but less than 60 MW, submitting bids is optional, although this is likely to also become obligatory.Source: Autoriteit Consument & Markt. (2023, September 25). ACM publiceert evaluatie congestiemanagement. ACM.

Participants are allowed to both bid for redispatching and balancing. However, if the bid for redispatching is used, participants need to withdraw their order for balancing. The awarded redispatch bids receive energy prices “pay-as-bid”.

- GOPACS

In 2019, the DSOs (Stedin, Liander, Enexis and Westland Infra), TenneT and the intraday trading platform ETPA developed and launched GOPACS. The platform is used both by TSO and DSOs.

Using the existing energy trading platforms from ETPA and EPEX SPOT, participants can place intraday bids. The buy and sell orders that are not matched and that can be used for redispatch are forwarded to GOPACS. Then, grid operators can adjust the production/consumption capacity of those participants based on their intraday bid.

In order to not affect the grid balance, the order is matched with an opposite order from a market party outside the congested area.

If congestion issues persist despite these measures, grid operators can manually contact asset owners to perform redispatch.

2. Differences & conflicts between balancing and congestion management

2.1. Differences

Balancing and congestion management share some similarities, particularly in their predominantly market-driven approaches. However, understanding their distinct characteristics is important to identify potential conflicts between them. Here, we outline their primary disparities:

- Nature of the issue: Imbalance arises when supply and demand of electricity don’t match, while congestion arises from overload (not enough transmission capacity).

- Geographical scope: Imbalance is an issue at a national scale. To solve it, the TSO uses balancing products which are also not locally bound and can be deployed anywhere in the Dutch network. Thus, selecting a balancing product is mainly based on its price (activate the cheapest products first). In contrast, congestion happens locally, and its management is also location-dependent (the effectiveness of a redispatch unit mainly correlates with its proximity to the congested point). Thus, when redispatch is based not only on a economical merit order, but also on a technical merit order.

- Timeframe: Balancing occurs in predetermined time frames such as day-ahead, intraday, or real-time. On the other hand, managing congestion is a continuous process. It goes from long-term planning (for projects such as grid extension and reinforcement) to real-time actions (using redispatch to solve local congestion at specific times).

- Product activation: While both congestion management and balancing require a fast activation of their products, the balancing resources are activated for a shorter period of time compared to congestion products.

- Procurement: Procurement of balancing products occurs through dedicated markets (FCR, aFRR, mFRR), whereas redispatch procurement varies from capacity contracts (like CBCs) to market-driven approaches.

2.2. When balancing and congestion management conflict

Balancing and congestion management have a common goal: ensuring a stable, reliable, and efficient energy supply. However, the interconnectedness of the energy system and the need for flexibility means that actions taken for one purpose can conflict with the other. For instance:

- A balancing service might not be provided by a generator because it’s used for congestion management. Balancing and congestion management are then competing for the same limited flexibility resources.

In other cases, balancing and redispatch resources might cancel each other out:

- A balancing product might not be activated due to requirements to reduce generation for congestion management purposes.

- A balancing product might, by being activated, increase the peak load and aggravate local congestion.

- Imbalance arises due to the curtailment of an asset for congestion management, and not enough balancing products were requested.

For a more concrete example, take the case of a surplus of electricity due to a lot of offshore wind. On the market, the dynamic prices will fall sharply for consumers. Based on this incentive, they might decide en masse to charge their home battery, car, boiler. While the demand will match the supply (grid balanced), this peak can cause local congestion.

Thus, to prevent conflicts, coordination is essential to enhance the compatibility and resource allocation efficiency of both systems.

3. The Teleport: unlocking asset flexibility

To participate in these markets, your assets must be controllable and responsive. The Teleport Gateway is the link that provides this flexibility.

It acts as a local energy management system (EMS), connecting your assets (solar, wind, or batteries) to your chosen energy partners (BRP, BSP, CSP…) through a single, secure API.

Additionally, its local control logic acts as your safeguard. The Teleport can execute a command from a national balancing market while simultaneously monitoring the local grid connection. If a market signal would violate your local physical limits, the Teleport automatically and instantly adjusts the command, ensuring you capture revenue without ever compromising the safety of your site.

Want to learn more? Visit the Teleport page.

4. Conclusion

As the energy transition continues, efficient grid balancing and congestion management become increasingly important.

While these functions have differences, it is imperative for stakeholders, market participants, and regulators to collaborate closely to harmonize these systems and ensure a reliable energy supply.

Want to learn more about the Dutch grid challenges?

Here are a few recommended readings:

Nederland

Nederland